The Crisis, No. 5

On the hollowing of Apple

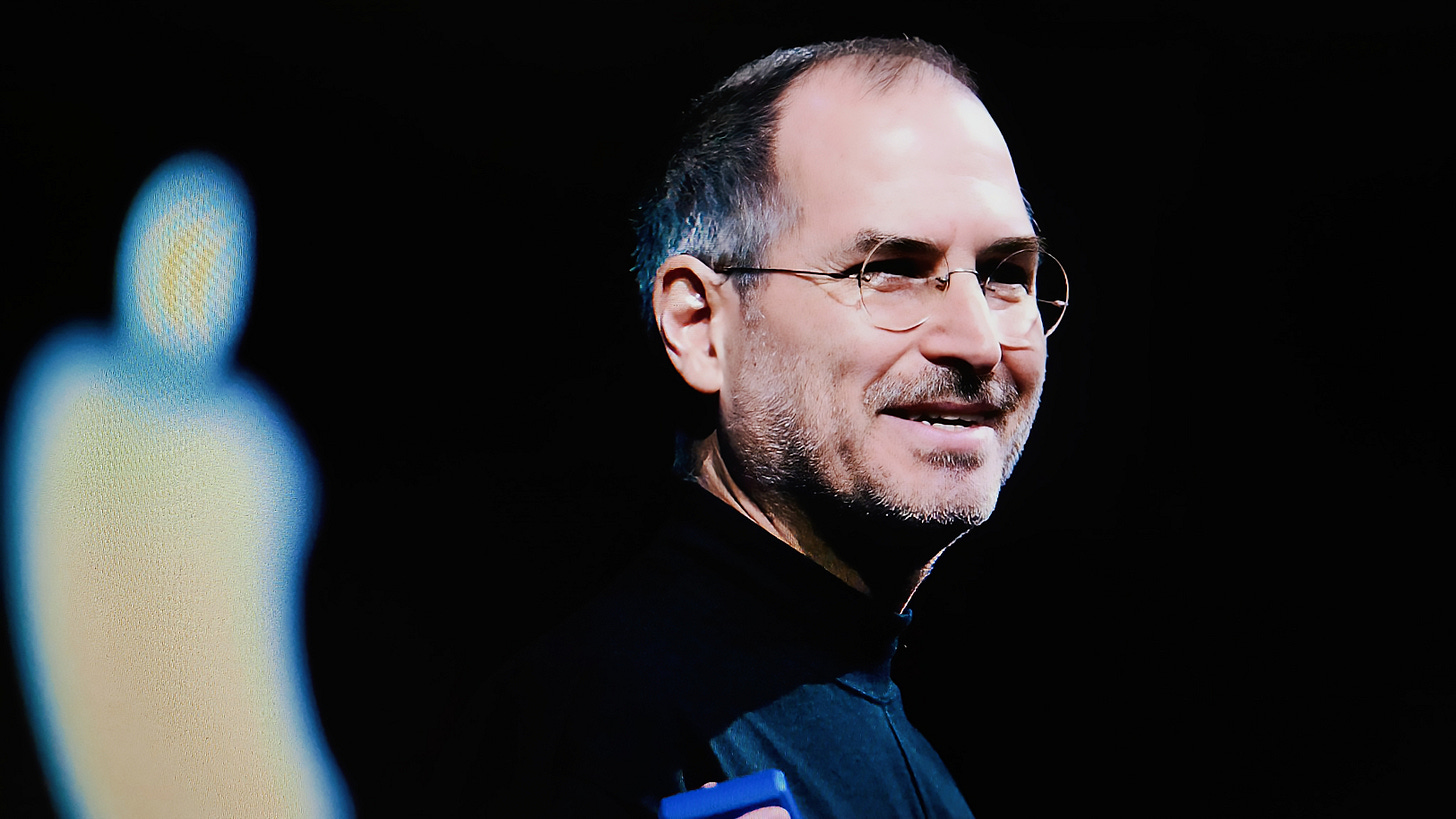

I never met Steve Jobs. But I know him—or I know him as well as anyone can know a man through the historical record. I have read every book written about him. I have read everything the man said publicly. I have spoken to people who knew him, who worked with him, who loved him and were hurt by him.

And I think Steve would be disgusted by what has become of his company.

This is not hagiography. Jobs was not a saint. He was cruel to people who loved him. He denied paternity of his daughter for years. He drove employees to breakdowns. He was vain, tyrannical, and capable of extraordinary pettiness. I am not unaware of his failings, of the terrible way he treated people needlessly along the way.

But he had a conscience. He moved, later in life, to repair the damage he had done. The reconciliation with his daughter Lisa was part of a broader moral development—a man who had hurt people learning, slowly, how to stop. He examined himself. He made changes. He was not a perfect man. But he had heart. He had morals. And he was willing to admit when he was wrong.

That is a lot more than can be said for this lot of corporate leaders.

It is this Steve Jobs—the morally serious man underneath the mythology—who would be so angry at what Tim Cook has made of Apple.

⁂

Steve Jobs understood money as instrumental.

I know this sounds like a distinction without a difference. The man built the most valuable company in the world. He died a billionaire many times over. He negotiated hard, fought for his compensation, wanted Apple to be profitable. He was not indifferent to money.

But he never treated money as the goal. Money was what let him make the things he wanted to make. It was freedom—the freedom to say no to investors, to kill products that weren’t good enough, to spend years on details that no spreadsheet could justify. Money was the instrument. The thing it purchased was the ability to do what he believed was right.

This is how he acted.

Jobs got fired from his own company because he refused to compromise his vision for what the board considered financial prudence. He spent years in the wilderness, building NeXT—a company that made beautiful machines almost no one bought—because he believed in what he was making. He acquired Pixar when it was bleeding cash and kept it alive through sheer stubbornness until it revolutionized animation.

When he returned to Apple, he killed products that were profitable because they were mediocre. He could have milked the existing lines, played it safe, optimized for margin. Instead, he burned it down and rebuilt from scratch. The iMac. The iPod. The iPhone. Each one a bet that could have destroyed the company. Each one made because he believed it was right, not because a spreadsheet said it was safe.

He told the record labels to accept his terms for iTunes or get nothing. He pulled Flash from the iPhone despite advertisers screaming. He refused to put ports and buttons on devices because he thought they were ugly, even when customers complained. He made choices that cost money, lost partnerships, and alienated people—because the alternative was making something he didn’t believe in.

This is what it looks like when money is instrumental. Not poverty. Not asceticism. But the willingness to light money on fire for what you believe is right—because you understand that money is only valuable for what it lets you do.

This essay is not really about Steve Jobs or Tim Cook. It is about what happens when efficiency becomes a substitute for freedom. Jobs and Cook are case studies in a larger question: can a company—can an economy—optimize its way out of moral responsibility? The answer, I will argue, is yes. And we are living with the consequences.

⁂

Jobs understood something that most technology executives do not: culture matters more than politics.

He did not tweet. He did not issue press releases about social issues. He did not perform his values for an audience. He was not interested in shibboleths of the left or the right.

But he cared deeply about what stories got told. He fell in love with Pixar because he understood that animation could shape how children see the world. He fought to preserve Lasseter’s creative vision against the suits who wanted to optimize for market research. He joined Disney‘s board because he understood that Disney was not just a company—it was a cultural institution with the power to define what Americans believe.

This is how Jobs approached politics: through art, film, music, and design. Through the quiet curation of what got made. Through the understanding that the products we live with shape who we become.

If Jobs were alive today, I do not believe he would be posting on Twitter about fascism. That was never his mode.

But I believe—I am certain—that he would be using Apple‘s enormous cultural power to resist it. Apple TV would be funding documentaries that exposed the corruption. Apple Music would be elevating artists who spoke truth. The company’s aesthetic weight, its prestige, its reach—all of it would be deployed, quietly and relentlessly, in service of the values Jobs actually held.

Not through corporate statements. Through culture. Through story. Through the patient work of shaping what people see and hear and believe.

That is what Steve would have done.

⁂

Tim Cook is a supply chain manager.

I do not say this as an insult. It is simply what he is. It is what he was hired to be. When Jobs brought Cook to Apple in 1998, he brought him to fix operations—to make the trains run on time, to optimize inventory, to build the manufacturing relationships that would let Apple scale.

Cook was extraordinary at this job. He is, by all accounts, one of the greatest operations executives in the history of American business. The margins, the logistics, the global supply chain that can produce millions of iPhones in weeks—that is Cook’s cathedral. He built it.

But operations is not vision. Optimization is not creation. And a supply chain manager who inherits a visionary’s company is not thereby transformed into a visionary.

Under Cook, Apple has become very good at making more of what Jobs created. The iPhone gets better cameras, faster chips, new colors. The ecosystem tightens. The services revenue grows. The stock price rises. By every metric that Wall Street cares about, Cook has been a success.

But what has Apple created under Cook that Jobs did not originate? What new thing has emerged from Cupertino that reflects a vision of the future, rather than an optimization of the past?

The Vision Pro is an expensive curiosity. The car project was canceled after a decade of drift. The television set never materialized. Apple under Cook has become a company that perfects what exists rather than inventing what doesn’t.

This is what happens when an optimizer inherits a creator’s legacy. The cathedral still stands. But no one is building new rooms.

⁂

There is a deeper problem than the absence of vision. Tim Cook has built an Apple that cannot act with moral freedom.

The supply chain that Cook constructed—his great achievement, his life’s work—runs through China. Not partially. Not incidentally. Fundamentally. The factories that build Apple‘s products are in China. The engineers who refine the manufacturing processes are in China. The workers who assemble the devices, who test the components, who pack the boxes—they are in Shenzhen and Zhengzhou and a dozen other cities that most Americans cannot find on a map.

This was a choice. It was Cook’s choice. And once made, it ceased to be a choice at all. Supply chains, like empires, do not forgive hesitation. For twenty years, it looked like genius. Chinese manufacturing was cheap, fast, and scalable. Apple could design in California and build in China, and the margins were extraordinary.

But dependency is not partnership. And Cook built a dependency so complete that Apple cannot escape it.

When Hong Kong’s democracy movement rose, Apple was silent. When the Uyghur genocide became undeniable, Apple was silent. When Beijing pressured Apple to remove apps, to store Chinese user data on Chinese servers, to make the iPhone a tool of state surveillance for Chinese citizens—Apple complied. Silently. Efficiently. As Cook’s supply chain required.

This is not a company that can stand up to authoritarianism. This is a company that has made itself a instrument of authoritarianism, because the alternative is losing access to the factories that build its products.

⁂

There is something worse than the dependency. There is what Cook gave away.

Apple did not merely use Chinese manufacturing. Apple trained it. Cook’s operations team—the best in the world—went to China and taught Chinese companies how to do what Apple does. The manufacturing techniques. The materials science. The logistics systems. The quality control processes.

This was the price of access. This was what China demanded in exchange for letting Apple build its empire in Shenzhen. And Cook paid it.

Now look at the result.

BYD, the Chinese electric vehicle company, learned battery manufacturing and supply chain management from its work with Apple. It is now the largest EV manufacturer in the world, threatening Tesla and every Western automaker.

DJI dominates the global drone market with technology and manufacturing processes refined through the Apple relationship.

Dozens of other Chinese companies—in components, in assembly, in materials—were trained by Apple‘s experts and now compete against Western firms with the skills Apple taught them.

Cook built a supply chain. And in building it, he handed the Chinese Communist Party the industrial capabilities it needed to challenge American technological supremacy.

This is the irony of Apple‘s China dependency. Cook created competitors. He trained the very companies that will, eventually, make Apple redundant. And now China slowly tightens the noose—raising costs, demanding more concessions, promoting domestic alternatives—while Apple cannot leave because Cook built a machine that only runs in China.

He optimized for efficiency and built a prison. Now he lives in it.

⁂

So when I see Tim Cook at Donald Trump’s inauguration, I understand what I am seeing.

When I see him at the White House on January 25th, 2026—attending a private screening of Melania, a vanity documentary about the First Lady, directed by Brett Ratner, a man credibly accused of sexual misconduct by multiple women—I understand what I am seeing.

I understand what I am seeing when I learn that this screening took place on the same night that federal agents shot Alex Pretti ten times in the back in Minneapolis. That while a nurse lay dying in the street for the crime of trying to help a woman being pepper-sprayed, Tim Cook was eating canapés and watching a film about the president’s wife.

Tim Cook’s Twitter bio contains a quote from Martin Luther King Jr.: “Life’s most persistent and urgent question is, ‘What are you doing for others?’”

What was Tim Cook doing for others on the night of January 25th?

He was doing what efficiency requires. He was maintaining relationships with power. He was protecting the supply chain, the margins, the tariff exemptions. He was being a good middleman.

I am seeing a man who cannot say no.

This is what efficiency looks like when it runs out of room to hide.

He cannot say no to Beijing, because his supply chain depends on Beijing’s favor. He cannot say no to Trump, because his company needs regulatory forbearance and tariff exemptions. He is trapped between two authoritarian powers, serving both, challenging neither.

This is not leadership. This is middleman management. This is a man whose great achievement—the supply chain, the operations excellence, the margins—has become the very thing that prevents him from acting with moral courage.

Cook has more money than Jobs ever had. Apple has more cash, more leverage, more market power than at any point in its history. If anyone in American business could afford to say no—to Trump, to Xi, to anyone—it is Tim Cook.

And he says yes. To everyone. To anything. Because he built a company that cannot afford to say no.

⁂

Steve Jobs would never have built this trap.

Not because he was naive about manufacturing—he wasn’t. Jobs understood supply chains. He hired Cook precisely because he understood their importance. And yes, Jobs used China too. He cared about scale. He was not some geopolitical purist operating from a position of ideological purity.

But Jobs would have kept his options open. It was something he always did. He had an aversion—deep in his soul—to being anyone’s bitch. Look at how he ran Apple: feet in multiple buckets, PowerPC and Intel simultaneously, never letting any single supplier or partner have him over a barrel. Look at how he cultivated competitive management structures beneath him—redundancy by design, because redundancy meant options, and options meant freedom.

He would have maintained leverage. He would have diversified. He would never have permitted a dependency so total that it foreclosed moral action.

And consider this: if Jobs had lived past 2011, he would have seen what happened to Hollywood. He would have seen movie scripts being submitted to Chinese censors before filming begins—an open secret in Los Angeles, a routine humiliation that studios accept because they want access to the Chinese market. You have to believe that Jobs, the man who guarded John Lasseter’s creative freedom at Pixar like a dragon guarding gold, would have bristled at such a thing. Would have pushed for other options. Would have refused to play that game.

Because that’s who he was. The fact that Steve was such an asshole is actually a feature, not a bug, in cases like this. His stubbornness, his tyranny, his refusal to accommodate—these were the qualities that would have prevented capture. Sucking authoritarian dick was simply not on Steve’s menu.

Cook happily became the CCP’s. And now he finds himself where he is: managing a morally impossible set of contradictions of his own making. Serving Beijing and Washington. Genuflecting to Xi and Trump. Wearing the MLK quote in his bio while watching vanity films on the night a nurse is executed.

The difference is not geography. It is leverage. Jobs used China without allowing China to use Apple. Cook transformed a tool into a master.

But Jobs also understood that moral freedom requires operational freedom. That you cannot act on your values if you have made yourself dependent on people who do not share them. That the price of efficiency, if the price is servility, is too high.

Would keeping options open have cost money? Yes. Would Wall Street have complained? Yes. Would Apple be worth less on paper? Probably.

But it would be free. And Jobs understood that freedom—the freedom to do what you believe is right—is worth more than margin.

⁂

I said at the beginning that Jobs would be disgusted. Let me be more specific.

Jobs would be disgusted that Apple, his company, the company he built and loved and bled for, has become an instrument of two authoritarianisms. That it serves Beijing’s surveillance state and Trump’s cruelty with equal compliance. That it has traded its soul for supply chain efficiency.

Jobs would be disgusted that Apple‘s cultural power—Apple TV, Apple Music, Apple News, the platforms that reach hundreds of millions of people—is deployed for nothing. That it sits inert while fascism rises, producing content that offends no one and moves no one and matters to no one.

Jobs would be disgusted that the man he chose to run operations has confused operations with leadership. That Cook believes the job is to make the trains run on time, when the job—the real job, the job that Jobs did—is to decide where the trains should go.

And Jobs would be disgusted that Cook, with all the resources in the world, has chosen to kneel.

⁂

I do not know what comes next for Apple. Perhaps Cook retires and a new leader emerges who remembers what the company was supposed to be. Perhaps the China trap tightens until Apple is merely a brand licensed to Chinese manufacturers. Perhaps none of this matters, and the stock price continues to rise, and shareholders remain happy, and the hollowing out proceeds invisibly.

But I know what I believe.

I believe that Steve Jobs built Apple to be something more than a company. He built it to be a statement about what technology could be—beautiful, humane, built for people rather than against them. He believed that the things we make reflect who we are. He believed that how we make them matters.

Tim Cook has betrayed that vision—not through malice, but by excelling in a system that rewards efficiency over freedom and calls it leadership. Through the replacement of values with optimization. Through the construction of a machine so efficient that it cannot afford to be moral.

Apple is not unique in this. It is exemplary.

This is what happens to institutions that mistake scale for strength, efficiency for freedom, optimization for wisdom. They become powerful enough to dominate markets—and too constrained to resist power. Look at Google, training AI for Beijing while preaching openness. Look at Amazon, building surveillance infrastructure for any government that pays. Look at every Fortune 500 company that issued statements about democracy while writing checks to the politicians dismantling it.

Apple is simply the cleanest case, because it once knew the difference. Because Jobs built it to know the difference. And because we can see, with unusual clarity, the precise moment when knowing the difference stopped mattering.

Steve Jobs was not a perfect man. But he built something that mattered. And he would be heartbroken to see what it has become.

I believe history will judge Tim Cook harshly. Not because he was evil—he is not—but because he had everything he needed to be good, and he chose to be efficient instead.

And efficiency, once chosen over freedom, never chooses back.

That is the betrayal of Apple. That is what Steve would have seen. That is what I see.

From Tim Cook, today:

"I’m heartbroken by the events in Minneapolis, and my prayers and deepest sympathies are with the families, with the communities, and with everyone that’s been affected.

This is a time for deescalation. I believe America is strongest when we live up to our highest ideals, when we treat everyone with dignity and respect no matter who they are or where they’re from, and when we embrace our shared humanity. This is something Apple has always advocated for. I had a good conversation with the president this week where I shared my views, and I appreciate his openness to engaging on issues that matter to us all.

I know this is very emotional and challenging for so many. I am proud of how deeply our teams care about the world beyond our walls. That empathy is one of Apple’s greatest strengths and it is something I believe we all cherish.

Thank you for all that you do."

No, Mr. Cook, I respectfully disagree. This is a time for escalation; for standing up for what is right, and moral, and just. It is not a time to "treat everyone with dignity and respect"; it is a time to show those who are failing to treat everyone with dignity and respect that their behavior will not be tolerated in this society. It is not a time for having "a good conversation" with a madman intent on turning our Republic into a dictatorship. While I am sure you are proud of "how deeply Apple teams care about the world", I am disappointed that you appear to care for nothing more than Apple's bottom-line next quarter profits, and will appease dictators on both sides of the Pacific to preserve and increase them.

(Sent to tcook@apple.com, because I have no fucks left to give.)

Wow....just WOW. What an incredibly insightful article. Thank you. You frame the issues we are dealing with in our society perfectly...issues that were becoming increasingly pernicious before Trump, but now that we have a full-on fascist assault on our democracy, these monster companies and their leader/oligarchs are gorging on what prosperity we have left here in the U.S. And the way you discuss what the real purpose, or value, of money should be... you have created many quotable quotes that I will use (with full credit). Thank you for your insights. Thank you for writing this. This is a piece that should be featured in Harvard Business Review.