The Banality of Bitcoin Advocacy

Yesterday, I wrote an essay. A meditative, reflective essay .Bitcoin is a lie, I said. An accusation. A moral charge. The responses have been enlightening, and have pushed me to follow-up with some more thoughts.

This morning, someone I am quite fond of, but someone who has grown wary of me, appealed to me in the epistemic Thunderdome, now called X (formerly Twitter). I can’t stop thinking about it. Not because it was particularly unusual—I’ve had versions of this conversation dozens of times with Bitcoin advocates who consider themselves progressive, who work in nonprofits, who teach in developing nations, who genuinely believe they’re fighting for freedom and human rights. But because this one proceeded with such clarity, such perfect philosophical precision, that it revealed something I’ve been trying to articulate for months.

It revealed how decent people become complicit in monstrous projects while insisting—with complete sincerity—that their good intentions make them different from the monsters.

The Exchange

The conversation is centered here. Not because I want to make this personal—Trey is emblematic of a much larger phenomenon—but because the specific moves he made, the precise structure of his moral reasoning, demonstrates something essential about how thoughtful people end up advancing authoritarian projects while convinced they’re doing the opposite.

Trey’s response to my essay was immediate and visceral: I was being “disingenuous,” focusing on “fringe extremes,” taking “the easy way out.” The piece, he said, was “like a half truth”—attacking Bitcoin itself rather than “truly focusing the attacks and arguments against people, government, Wall Street.”

I told him I resented being called dishonest. That I understand what “disingenuous” means, and that I was offended by the allegation of intellectual corruption.

His response revealed the first layer of his reasoning: “What is the right team then, Mike? To disregard this open source tool that has incredible merit, use, and action in the world? One could argue there is no ‘team’ Bitcoin. It’s merely a tool.”

I asked if he was familiar with the concept of begging the question.

Because embedded in his response—”what is the right team then?”—was a complete normative framework he hadn’t examined. The question assumed that the status quo is so bankrupt, so morally compromised, that any alternative tool must be embraced regardless of who else is building it or why.

This is what philosophers call a “normative embedding.” Behind his question lay an unexamined assumption: that the current system represents the summum malum—the greatest evil—and therefore any disruption of it, any tool that might undermine it, must be supported even if that means working alongside people whose explicit goal is ending democratic governance.

I wrote back: “Behind your question is what philosophers might call a ‘normative embedding.’ I can see it in your stance. It’s implicit. The embedding is this: the status quo is bankrupt. In moral philosophy terms, you have made the status quo your summum malum.”

“And from here, your calculation of moral compromise becomes clear. That you are better to work alongside the very people my piece makes moral charge against, in common cause with them. You have walked deep into the territory of ‘the lesser evil’. The place where you say to yourself: perhaps it’s best, I work alongside these fascists now, even as I disagree with them, because I believe the greater good, my summum bonum goal will redound to my moral worldview, and things will work out once the status quo is dispatched, by this common cause.”

The Retreat to Personal Purity

His response was revealing: “What fascists am I ‘working alongside’ with Mike? The fascists on the board of the progressive bitcoiner, or teachers and educators in the bitcoin space across Latin American and Africa? I’m literally just telling people about bitcoin as freedom tech, and I work in nonprofits.”

Do you see the move? When confronted with the documented alliance between Bitcoin advocacy and neo-reactionary politics, he retreated immediately to personal credentials. To the sympathetic individuals he works with. To his nonprofit status. To his local activities.

As if working with teachers in Africa immunizes him from responsibility for the broader political project he’s advancing. As if his good intentions change what he’s building or who it serves.

I responded directly: “You advocate for a Bitcoin monetary order. Peter Thiel, Curtis Yarvin, and an entire constellation of neo-reactionaries explicitly advocate for the same monetary order as part of their project to dismantle democratic governance and return to hierarchical rule. You are promoting the same end they are promoting. That is what ‘working alongside’ means—not that you share their intentions, but that you share their goal and help build the infrastructure they need.”

The Confession

What happened next was extraordinary. Trey didn’t deny the alliance. He didn’t dispute that neo-reactionaries see Bitcoin as essential to their project. Instead, he made an admission that should terrify anyone who cares about democratic governance:

“I think you’re mistaken. There’s a difference between advocating for a totalitarian, monarch, anarcho capital [sic] worldview, frame, etc. And seeing Bitcoin as a potential answer and solution. I do not wish for this monetary disruption that would potentially cost millions of lives.”

This is a confession. He doesn’t dispute the structural implication—that Bitcoin represents “monetary disruption that would potentially cost millions of lives.” He doesn’t dispute that he’s advocating for the same system the neo-reactionaries want. And his defense—his entire moral framework—rests on the claim that his intentions are different from theirs.

He doesn’t wish for millions to die. He just advocates for a system that might kill them. But because his heart is pure, because he means well, because he works with teachers and nonprofits, somehow this makes him different from the people who want the same disruption for explicitly authoritarian purposes.

The Space Where Arendt Becomes Unavoidable

I didn’t want to go here. I gave Trey multiple opportunities to step back, to examine what he was saying, to consider the implications of advocating for catastrophic disruption while hiding behind good intentions.

But he kept doubling down. Kept insisting that his local good works, his progressive credentials, his pure motivations made him fundamentally different from the fascists who need the same infrastructure he’s building.

And at some point, when someone keeps making that argument—when they keep insisting that meaning well excuses the refusal to examine consequences—you have to name what they’ve become.

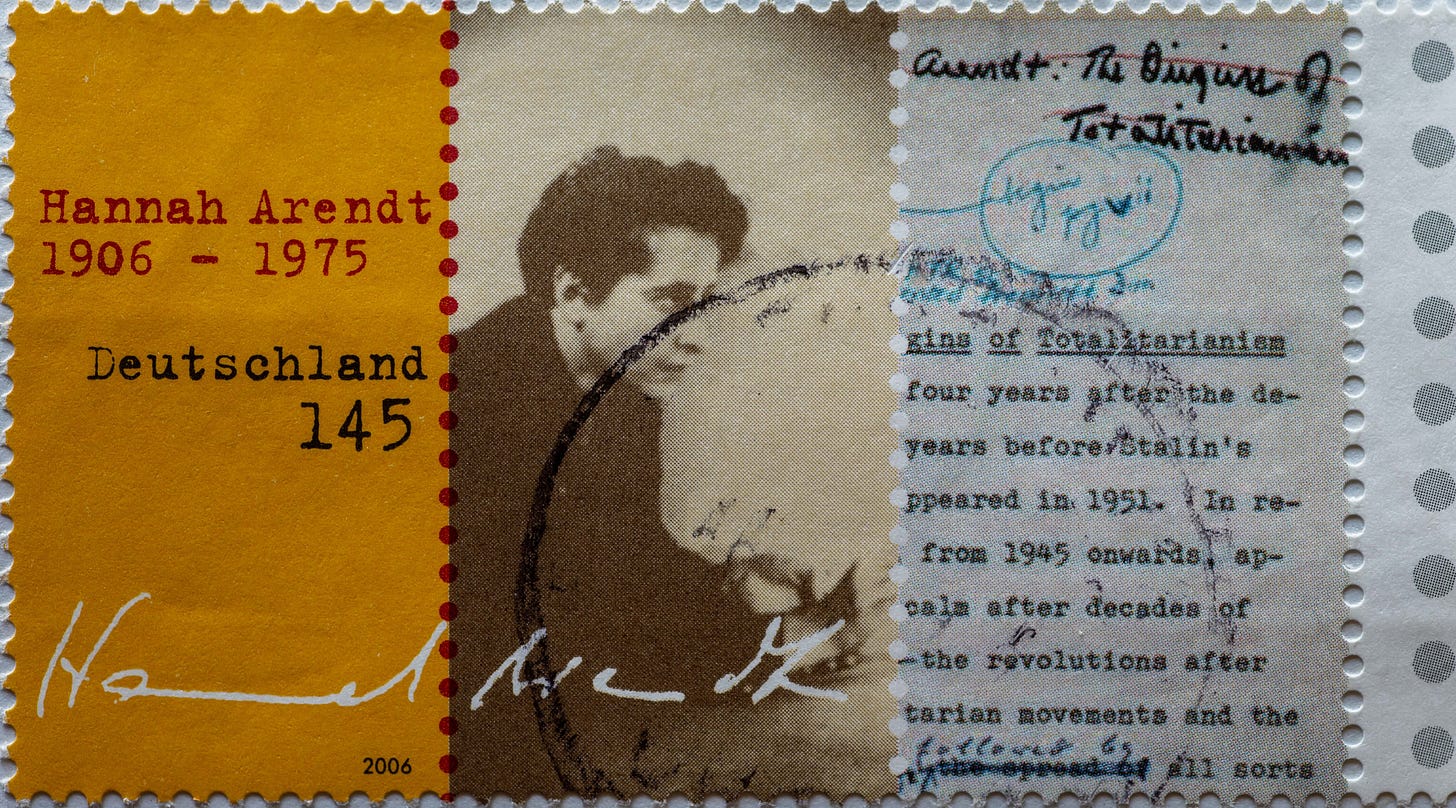

Hannah Arendt spent years studying Adolf Eichmann, trying to understand how the Holocaust happened. Not through monsters, but through bureaucrats. Through people who saw themselves as competent, diligent, just doing their jobs. Through people who had paperwork to file, logistics to manage, trains to schedule.

Her conclusion—the insight that made Eichmann in Jerusalem so controversial—was that evil doesn’t require malicious intent. It doesn’t require cruelty or sadism or hatred. It requires only the refusal to think. The failure to examine what you’re part of. The insistence that doing your job, following procedures, meaning well is sufficient moral justification.

Eichmann wasn’t a monster. He was banal. He was ordinary. He was someone who refused to look at what his bureaucracy was doing, who focused on his competence at his narrow task, who probably thought of himself as a decent person caught in difficult circumstances.

The banality of evil—the phrase that became Arendt’s most famous contribution to moral philosophy—isn’t about evil being unimportant or trivial. It’s about evil emerging from thoughtlessness. From the refusal to follow chains of consequence. From hiding behind process, behind duty, behind good intentions.

Attention as Moral Choice

There’s a reason Holocaust survivors chant “never look away.” Not just as a reminder about the past, but as a moral instruction about the present.

Looking away isn’t passive. It’s an active choice about what you’ll allow yourself to see, what you’ll take responsibility for, what you’ll examine versus what you’ll keep comfortably out of focus.

Trey has been shown exactly what to look at. The neo-reactionaries who share his Bitcoin goal. What they want to build with it. Why they need it for their vision of hierarchical rule. The consequences he himself admits might include millions of deaths. The infrastructure he’s helping create that they require

His response? “Look at my nonprofit work instead. Look at the teachers I work with. Look at my good intentions.”

Arendt rolls ever so slightly in her grave. Here, the choice to look away would require abandonment of identity—of the self-conception as progressive advocate, as freedom fighter, as someone on the right side of history. So instead he looks selectively, focusing deliberately on what makes him feel good rather than examining what his actions actually do.

The Holocaust survivors understand this viscerally: evil depends on people looking away. On people focusing on their narrow duties, their local kindness, their personal virtue—anything except the machinery they’re part of and what that machinery does.

No Freedom Without Responsibility

Here’s the philosophical foundation that makes all of this matter: self-governance—whether individual or collective—requires taking responsibility for consequences, not just intentions.

You cannot say “I meant well” and expect that to substitute for moral reasoning. You cannot say “I’m pro-democracy” while building infrastructure for people who explicitly want to end democracy. You cannot say “I care about freedom and human rights” while refusing to examine whether your actions actually serve those values.

Freedom and responsibility are complementary. You don’t get one without the other. This is the heart of liberal democratic theory—that citizens can govern themselves because they’re capable of reasoning about consequences, capable of taking responsibility for their choices, capable of examining their role in systems and adjusting accordingly.

Trey wants the freedom to advocate for Bitcoin without the responsibility to examine what Bitcoin advocacy actually serves. He wants credit for his stated values without accountability for his actual choices. He wants to be judged by his intentions while refusing to look at his consequences.

This is a moral abdication.

The person who says “I meant well, don’t hold me responsible for consequences I refused to examine” has abandoned the very principle that makes democratic self-governance possible. Has opted out of the hard work of thinking about what you’re doing and whether it coheres with what you claim to value.

Good intentions are not an excuse. They never were. They can’t be. Because if they were, then no one would ever be responsible for anything except explicit malice. And that’s not a world where freedom is possible—it’s a world where thoughtlessness becomes the perfect alibi for complicity.

The Question They Won’t Ask

Throughout this exchange, there’s one question Trey never addressed. The question I keep asking Bitcoin advocates, the one they always dodge:

Why do fascists love Bitcoin?

Why is the monetary system you’re building so appealing to people who explicitly want to destroy democratic governance and return to hierarchical rule? Why do Curtis Yarvin and Peter Thiel—people who write that democracy and freedom are incompatible, who advocate for corporate monarchy, who want to replace democratic accountability with rule by cognitive elites—why do they see Bitcoin as essential infrastructure for their vision?

This isn’t a rhetorical trick. It’s a genuine question about the nature of what you’re building. When the people who want to end democracy think your tool is critical to that project, shouldn’t you at least examine why? Shouldn’t you at least consider whether there’s something about the system itself—not just who’s using it, but its inherent characteristics—that serves authoritarian rather than democratic ends?

But Trey won’t ask this question. Can’t ask it. Because asking it would require looking at what he’s actually building rather than what he hopes he’s building. It would require examining whether “freedom tech” might actually mean “freedom for capital from democratic oversight” rather than “freedom for people from oppression.”

It would require the kind of thinking that might lead to uncomfortable conclusions about his life’s work.

So he looks away. Focuses on his teachers and his nonprofits. Points to his intentions. Performs outrage that anyone would suggest he’s complicit in something he doesn’t intend.

The Useful Idiot

There’s a reason the useful idiot is more dangerous than the explicit fascist. The fascist at least makes clear what he wants—you can see him coming, organize against him, understand what you’re fighting.

But the useful idiot—the progressive Bitcoiner, the nonprofit worker, the well-meaning advocate who provides the human face for authoritarian projects—he makes the fascist project seem reasonable. Diverse. Even progressive.

“Look,” the argument goes, “it’s not just right-wing billionaires who support Bitcoin. There are teachers using it in Africa! Nonprofits accepting it! Progressive people building on it! How could it be a tool for neo-feudalism when such nice people are involved?”

This is the cover the fascist project needs. Not just explicit advocates but decent people who can be pointed to as evidence that the project isn’t what critics say it is.

Trey provides that cover. Not because he’s secretly authoritarian, but because he refuses to think about what he’s actually doing. Because he prioritizes his self-image as a good person over examining whether his actions serve good ends.

The Thiels and Yarvins of the world need people like Trey. They need the progressive Bitcoiners who will insist it’s “just a tool,” who will point to humanitarian uses, who will perform outrage when anyone suggests they might be advancing an authoritarian project.

They need people who will build the infrastructure while refusing to examine what it’s for.

A Failure of Character

I have empathy for Trey. I believe his stated values are sincere. I don’t think he set out to aid fascism or advance neo-feudalism. I recognize he’s confused rather than malicious, that he genuinely believes Bitcoin advocacy serves freedom and democracy.

But empathy can only go so far.

At some point, after you’ve been shown the coalition you’re in, after you’ve been asked why fascists need what you’re building, after you’ve admitted the stakes might include millions of lives—at some point, the refusal to look becomes not confusion but choice.

Trey has been given every opportunity to examine his position: To look at who shares his goal and why. To ask why neo-reactionaries see Bitcoin as essential. To consider whether “monetary disruption” that might kill millions coheres with his stated values. To confront the contradiction between building authoritarian infrastructure and claiming to support democracy

He’s chosen not to look. Chosen to focus on his intentions instead of his actions. Chosen to point to his local good works rather than examining his role in broader systems.

That’s a failure of character. Not in the sense of being a bad person, but in the sense of failing to exercise the moral responsibility that democratic citizenship requires.

Character, in the classical sense, means the capacity to think about what you’re doing and take responsibility for it. To examine your choices and their consequences. To maintain coherence between your stated values and your actual actions.

Trey wants democratic freedoms without democratic responsibilities. Wants to advocate for systemic change without examining whether that change serves his values. Wants credit for meaning well without accountability for what he’s helping build.

That’s not character. That’s its absence.

Correcting the Record

Jimmy Song has also responded, revealing a private conversation to suggest my critique stems from political partisanship rather than philosophical examination. Let me correct the record about what actually happened.

The conversation Jimmy references took place in the Norwegian Arctic, at a retreat attended by wealthy, influential people and human rights activists. There, in the unending sunlight of the Arctic summer, Jimmy advanced a forceful defense of the philosophical concept of self-ownership—arguing that it should supersede any notion of democratic control of property.

He calls me a “progressive.” I bristle at this characterization. My view is grounded in the classical liberal tradition—the framework that holds that free people can govern themselves through reason, deliberation, and democratic institutions. The tradition that Jimmy’s project seeks to actively destroy.

Because let’s be clear about what “self-ownership supersedes democratic control” actually means: it means property rights are absolute and prior to democratic decision-making. It means that if you own something, democratic majorities have no legitimate authority to regulate it, tax it, or impose conditions on its use. It means that accumulated capital becomes a veto over collective self-governance.

This is just feudalism, when you strip it of all the pretensions of freedom, built atop a false religion of market supremacy.

Classical liberalism—from Locke through Mill through Rawls—recognizes that property rights exist within frameworks of democratic accountability. That liberty requires institutions constraining power concentration. That self-governance means citizens collectively determining the rules under which they live, including rules about property and its obligations.

The libertarian project Jimmy represents claims the mantle of “freedom” while building philosophical infrastructure for oligarchy. For a world where those who control capital are accountable to no one, where democratic institutions have no legitimate authority over property, where “self-ownership” becomes the alibi for unlimited accumulation without social obligation.

And here’s what makes the Norwegian Arctic setting so symbolically perfect: a gathering of wealthy people and their philosophical defenders, arguing in a place most people will never visit, about why democratic majorities shouldn’t be able to regulate their property. The physical remove mirrors the ideological one—discussing human freedom from a position so far removed from how most humans actually live that it becomes abstraction rather than lived reality.

Jimmy frames my defense of democratic institutions as “progressive” politics. But defending the principle that people should be able to govern themselves collectively, that property rights exist within democratic frameworks, that accumulated power requires accountability—this isn’t progressive radicalism. This is the center of liberal democratic theory.

What’s radical is the position Jimmy was defending: that self-ownership supersedes democratic control. That property rights are absolute. That Bitcoin represents the technological instantiation of these principles, creating a monetary system that places capital beyond democratic reach.

He’s right that I questioned libertarian premises even while working on Bitcoin. I questioned Austrian economics. I defended the legitimacy of democratic institutions to regulate markets and protect collective interests.

I call this intellectual honesty—refusing to treat Bitcoin advocacy as requiring total ideological conversion to a philosophical framework I found incoherent and dangerous.

What changed wasn’t my political orientation. What changed was my recognition of what Bitcoin advocacy has become—not just a technology but a political project aligned with those who explicitly reject democratic governance. When I started noticing Silicon Valley intellectuals discussing feudalism, when I read Thiel writing that democracy and freedom are incompatible, when I saw the coalition forming—I had to choose between looking away or examining what I was part of.

Jimmy suggests I lacked independent judgment, that I only liked Bitcoin because Jack Dorsey convinced me. But taking time to be persuaded by arguments demonstrates intellectual care. And reaching different conclusions after examining evidence demonstrates intellectual honesty.

The fact that his response to my philosophical argument is to reveal private conversation, question my motives, and mischaracterize my position as “progressive” rather than classical liberal tells you everything about which of us is engaging the substance.

I’m defending the proposition that free people can govern themselves democratically. Jimmy is defending the proposition that property supersedes democracy.

One of these positions is liberal. The other is feudalism wearing the costume of freedom.

My Own Complicity

I know what it’s like to be inside the system, believing you’re building something good. I was a tech executive. I worked on cryptocurrency projects in my career. I believed in markets and optimization and the power of technology to solve problems. I was one of those useful idiots, convinced my good intentions and technical competence made me different from the people using the same tools for authoritarian ends.

The conversation in the Arctic was clarifying. Not because it changed my mind in the moment, but because it revealed something I couldn’t ignore. When smart people start casually discussing feudalism, when billionaires write that democracy and freedom are incompatible, when your coalition includes people publishing blueprints for corporate monarchy—at some point you have to choose between looking away or examining what you’re actually part of.

I chose to look. And what I saw was uncomfortable enough that I walked away from everything I’d built. The recruiters stopped calling. Professional opportunities disappeared. I lost the insider status, the comfortable salary, the ability to tell myself I was one of the good guys inside the system making it better.

I’m ashamed of who I became during those years. I’m trying to make peace with my conscience. So when I tell you to look at what you’re building—I’m not speaking from some position of moral superiority. I’m speaking as someone who knows exactly how comfortable it is not to look, and exactly what it costs when you finally do.

People mistake my unwillingness to give ground on epistemic and moral hygiene as meanness, as arrogance, as narcissism. But this isn’t about being harsh. It’s about refusing to participate in the comfortable fiction that good intentions excuse the failure to examine consequences.

Sometimes stopping pain involves discomfort. Most of us won’t admit this to ourselves. We want to deny that we live in the tragic dimension—that there’s no comfortable way to do what’s right, that moral responsibility sometimes requires sacrifice that most people won’t make.

I made that sacrifice. Not because I’m better than anyone else, but because I couldn’t live with myself if I didn’t. Because intellectual honesty required it. Because looking away would have meant becoming exactly what Trey has become—someone who builds authoritarian infrastructure while insisting his heart is pure.

The Center Holds Through Looking

The center—the institutional and epistemic space where democratic self-governance remains possible—holds not through optimal positioning but through conscious choice. Through people who refuse to look away from uncomfortable truths. Who take responsibility for their role in systems. Who maintain the discipline to examine whether their actions cohere with their values.

It holds through people who understand that meaning well is necessary but not sufficient. That good intentions don’t excuse the failure to think. That freedom requires responsibility for consequences, not just purity of motive.

The Bitcoin advocates who insist it’s “just a tool” while refusing to examine who needs the tool and why—they’re not holding the center. They’re abandoning it. They’re opting out of the hard work of democratic reasoning in favor of hiding behind technical features and good intentions.

The center holds when people ask hard questions: What am I building? Who does it serve? Why do authoritarians love it? Do my actions cohere with my values? Am I taking responsibility for foreseeable consequences or hiding behind the claim that I didn’t intend them?

These aren’t comfortable questions. They require genuine examination that might lead to uncomfortable conclusions about your life’s work, your professional identity, your chosen community.

But they’re the questions democratic citizenship requires. The questions that distinguish self-governance from moral abdication.

Never Look Away

Two plus two equals four. There are twenty-four hours in a day. And Bitcoin advocacy has become inseparable from a neo-reactionary political project that explicitly aims to end democratic governance.

You can work with teachers. You can run nonprofits. You can mean well with every fiber of your being.

None of that changes what you’re building or who it serves. None of that excuses the refusal to examine the coalition you’re in and the infrastructure you’re creating.

Attention is a moral choice. Looking at what you’re part of is a moral obligation. Taking responsibility for foreseeable consequences is what democratic citizenship requires.

The Holocaust survivors understood this. Arendt understood this. Anyone who’s watched decent people advance monstrous projects while insisting they meant well understands this.

Evil doesn’t require malicious intent. It requires only the refusal to think. The failure to look. The insistence that meaning well is sufficient while you build the infrastructure that authoritarians need.

Never look away from what you’re building. Don’t hide behind good intentions. Don’t point to your local kindness while refusing to examine your global consequences.

The circus continues. The wire still holds for those willing to walk it with eyes open. But it requires the courage to look at what you’re actually doing, not just what you hope you’re doing.a

May we find that courage. Before it’s too late to matter.

Because millions of lives—by Trey’s own admission—might depend on people like him finally opening their eyes.

'Self-ownership' is one of the most intellectually and morally incoherent ideas in the complex mix of bad ideas cohabiting parasitically with good one that afflicts our society. To 'own' something is to be separate from it so as to exercise control and influence over it. Robert Nozick used this logic to argue it is OK to voluntarily sell oneself into slavery. Most libertarians loved his book 'Anarchy, State, and Utopia.'

But who exercises control over your self so as to own it?

A self exists as an in individual expression of relationships, some of which, were they different, would result in a very different self. My self is what it is because of where I grew up, the key people who influenced my life, my physical capabilities, and more. It is a pattern emerging from its history, not a thing to which events happen. It is more verb than object. One can own an object but not own a verb.

That means I cannot separate my self from anything but its immediate context, and the thought that I can arises from pretty superficial thinking.

I used to be a libertarian myself until I finally grasped that all its good words about freedom and such completely ignored the contexts within which we acted. At that point I finally grasped why so many libertarians are actually more sociopaths than respecters of human well-being.

Excellent piece. I honestly know little about Bitcoin, but I do know how currencies work; and this isn’t it: Bitcoin is a ponzo scheme.

That said, freedom for guys like Thiel appear to be only about two things:

1. Freedom for them is to do as they please; completely unregulated, regardless of what they destroy.

2. To create a monetary system which would give them control over nations. They aren’t just trying to destroy democracy, they’re trying to destroy the world order.