Clear Thinking v. Jordan Peterson

The Tragedy of Wasted Insight

This is, after all, a philosophy blog.

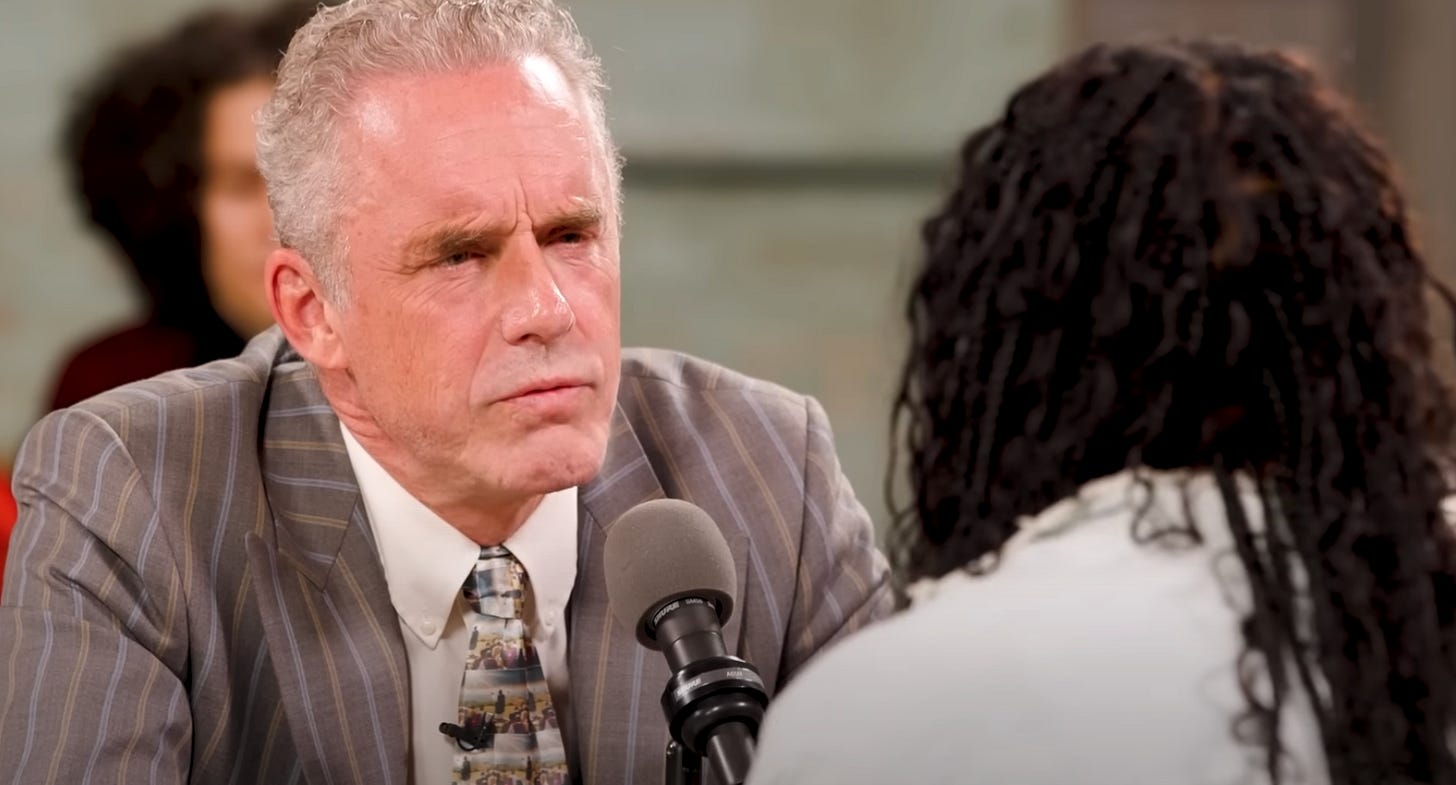

I've been going back and forth on whether I would write a Clear Thinking piece on Jordan Peterson. Then I sat through the entire episode of Jordan Peterson on Jubilee's Surrounded. I am embarrassed to admit that I understand what Peterson is trying to say. And yes, he actually has a point. I say this, as a self-identified atheist.

But understanding what someone is trying to say and agreeing that their method serves truth are two very different things. The real tragedy here is that Peterson is actually close to a serious insight. In some ways, he has accurately identified the territory that sits at the center of the true crisis of modernity—the same territory I've been exploring through my own mythopoetic experiments here at Notes From The Circus.

And that's what makes his approach so frustrating, and so dangerous.

The Territory Peterson Has Correctly Identified

Peterson recognizes something crucial that many secular thinkers miss: that the collapse of traditional meaning-making structures doesn't automatically produce rational, enlightened citizens. Instead, it often leaves people vulnerable to nihilistic despair, authoritarian simplicity, or the unconscious adoption of frameworks they don't recognize as frameworks at all.

He understands that meaning is constructed rather than discovered—that human beings are fundamentally meaning-making creatures who create significance through their choices, attention, and the stories they tell about their lives. He sees that the frameworks we use to interpret reality, whether religious or secular, shape not just what we think but how we live.

He recognizes that atheists often reject caricatures of religious belief rather than engaging with its more sophisticated formulations. That dismissing all religious insight as primitive superstition misses something important about how humans actually navigate questions of meaning, morality, and ultimate purpose.

Most importantly, he grasps that humans are mythopoetic creatures—that we need narrative frameworks, symbolic systems, practices that engage more than just our analytical faculties. That pure rationalism and pure emotivism are both inadequate for navigating the complexity of human existence.

These are real insights. They deserve serious engagement. And they're insights I've been wrestling with in my own work on democratic meaning-making, the Grand Praxis, and what I've called “secular liturgy.”

The Crucial Difference: Intellectual Honesty

But here's where Peterson and I part ways fundamentally: where he retreats into definitional fog, I advance into clarity. Where he uses complexity to avoid commitment, I use it to deepen engagement. Where he performs profundity, I attempt to practice it.

Peterson takes these legitimate observations about human meaning-making and weaponizes them through what can only be called sophisticated evasion. He uses the complexity of meaning-making to avoid answering simple, direct questions about what he actually believes and why.

Watch how this works in practice:

Atheist: “Do you believe in God?”

Peterson: “Well, what do you mean by God? And what do you mean by believe? Because if you mean...”

Atheist: “Do you think Jesus literally rose from the dead?”

Peterson: “That depends on what you mean by literally, and what you mean by death, and whether you understand the symbolic significance of resurrection as a pattern that...”

Atheist: “Would you lie to save innocent lives?”

Peterson: “That's a hypothetical stripped of context that forces me into an impossible moral choice, and if you present me with intractable dilemmas...”

This isn't intellectual humility. This isn't sophisticated thinking about complex questions. This is evasion disguised as profundity.

The Definitional Shell Game

Peterson's core technique is what I call the “definitional shell game.” He provides definitions that are so broad they become meaningless, then switches between broad and narrow definitions depending on what serves his argument in the moment.

“God” becomes anything you prioritize. “Worship” becomes any form of attention. “Christian” becomes anyone who acts with voluntary self-sacrifice, regardless of what they actually believe about Christ, resurrection, or any specifically Christian claims. "Religious" becomes anyone who cares about deep questions.

Under these definitions, Richard Dawkins becomes Christian (as Peterson explicitly states), atheists become religious (because they care about truth), and everyone becomes a worshipper (because everyone prioritizes something).

This isn't insight—it's category error elevated to philosophical method. It's like saying “everyone is a musician because everyone makes sounds” and then acting as if this profound observation tells us something meaningful about the difference between John Coltrane and a car alarm.

Why This Matters More Than Academic Debate

The reason this matters isn't that Peterson is wrong about everything—he's not. It's that he uses legitimate insights to protect illegitimate conclusions from serious scrutiny, and in doing so, he prevents us from having the conversation we desperately need to have about meaning-making in a post-traditional world.

Peterson wants to claim that atheists “don't understand what they're rejecting” while simultaneously defining religion so broadly that rejection becomes impossible. He wants to argue that Christian morality is foundational to Western civilization while avoiding any commitment to specifically Christian truth claims. He wants the cultural authority that comes from religious insight without the intellectual responsibility that comes from making falsifiable claims about reality.

This is sophisticated bad faith. It's the intellectual equivalent of having your cake and eating it too—claiming the benefits of religious belief while avoiding the costs of actually believing anything specific enough to be wrong about.

The Conversation That Never Happens

What's most frustrating about Peterson's approach is that it prevents the conversation we actually need to have. There are genuine questions about meaning, morality, and the role of traditional frameworks in human life that deserve serious exploration.

Can secular frameworks provide adequate foundations for meaning and morality? What do we lose when traditional religious structures collapse? How do we navigate questions of ultimate purpose in a universe that offers no predetermined answers? What does it look like to create new meaning-making frameworks that incorporate the wisdom of religious traditions while maintaining intellectual honesty about what we can and cannot know?

These are the questions that drive my work at Notes From The Circus. The development of what I call “secular liturgy”—practices that develop human capacity for meaning-making without requiring supernatural beliefs. The exploration of love as an epistemic force—a way of understanding reality that's more than analytical but not less than rational. The recognition that “we have no king” and must learn to govern ourselves, individually and collectively, through conscious meaning-creation rather than inherited authority.

But Peterson's definitional fog makes it impossible to engage with these questions productively. Instead of clarifying what's at stake in choosing between religious and secular approaches to meaning, he blurs the distinctions until no real choice is possible. Instead of helping us develop new frameworks adequate to our current moment, he offers elaborate justifications for pretending we don't need them.

The Alternative: Honest Mythopoesis

My work at Notes From The Circus represents what Peterson's approach could become if it had the courage of its convictions. I'm not hiding behind broad definitions that make everything religious and nothing specifically so. I'm creating new forms of meaning-making that acknowledge their constructed nature while taking responsibility for their content.

I'm not claiming that atheists are secretly Christian—I'm showing what secular meaning-making looks like when it's done with the same depth and seriousness that religious traditions brought to the task. I'm not defending traditional frameworks against modern critique—I'm developing new frameworks that incorporate what was valuable in the old while honestly acknowledging what must be left behind.

The circus metaphor, the secular liturgy, the integration of philosophical insight with narrative power—these represent genuine mythopoesis. The conscious creation of meaning-making frameworks that serve human flourishing without requiring intellectual dishonesty.

When I write “We shall never surrender” or develop the concept of love as an epistemic force, I'm not trying to make secular thinking sound religious. I'm showing what secular thinking becomes when it takes on the full responsibility of meaning-making that religious thinking once carried.

The Real Stakes

The real crisis of modernity isn't that people have stopped believing in God—it's that they've stopped believing they're capable of creating meaning worthy of their lives. Peterson's approach, for all its sophistication, ultimately reinforces this despair by suggesting that meaning requires frameworks you can't honestly affirm while making honest affirmation impossible through definitional sleight of hand.

This is why his approach is more than just intellectually dishonest—it's spiritually damaging. It tells people that their choice is between traditional religious frameworks they can't intellectually accept and secular frameworks that can't provide adequate meaning. It makes genuine alternatives invisible by defining the terms of debate so that no genuine choice is possible.

The alternative I'm developing suggests something different: that we are capable of creating meaning, that the work of meaning-making is our responsibility and our privilege, that secular frameworks can be every bit as profound and transformative as religious ones when they're developed with sufficient care and commitment.

What Clear Thinking Actually Looks Like

Clear thinking about these questions requires something Peterson consistently avoids: intellectual courage. The willingness to make specific claims that could be false. The honesty to acknowledge what you actually believe rather than hiding behind definitions broad enough to include everything and therefore mean nothing.

If you think God exists, say so and explain what you mean. If you think Jesus rose from the dead, own that belief and its implications. If you think Christian frameworks provide something secular ones can't, specify what that something is and why alternatives are inadequate.

If you can't or won't do these things, then you're not actually defending religious belief—you're performing a sophisticated form of intellectual cowardice that uses religious language to avoid religious commitment.

But the same standard applies to secular meaning-making. If you think human beings can create meaningful lives without supernatural beliefs, show what that looks like in practice. If you think democratic self-governance is possible, demonstrate the capacities it requires. If you think love is more than biochemistry, develop frameworks that honor its depth without retreating into mysticism.

This is what I've been attempting with Notes From The Circus—not to prove that secular frameworks are superior to religious ones, but to show what they become when they take full responsibility for the work of meaning-making.

The Tragedy of Wasted Insight

The tragedy is that Peterson could be contributing to this genuinely important work—the development of post-traditional meaning-making frameworks that integrate the insights of religious wisdom with the honesty of secular inquiry. His recognition of the crisis is accurate. His understanding of human mythopoetic needs is sophisticated. His grasp of what's at stake in the collapse of traditional frameworks is profound.

But instead of using these insights to help create new possibilities, he uses them to prevent the hard work that such creation requires. He wants the authority of religious insight without the responsibility of religious belief. The cultural power of Christian symbolism without the intellectual cost of Christian commitment. The benefits of traditional frameworks without the hard work of developing new ones.

He's become a sophisticated apologist for avoiding the very work his own insights suggest is necessary.

What's Really at Stake

We're living through a moment when the old frameworks for meaning-making are collapsing and new ones haven't yet stabilized. This creates both danger and opportunity—danger that people will retreat into authoritarian simplicity or nihilistic despair, opportunity to create something better than what came before.

Peterson has identified this moment correctly. But his response—to blur the distinctions between old and new frameworks until no real choice is possible—prevents us from seizing the opportunity his own analysis reveals.

The work we need to do is difficult: creating new forms of meaning-making that are adequate to our current knowledge while serving our deepest needs. Developing secular frameworks that can provide the depth and transformative power that religious frameworks once offered. Learning to govern ourselves—intellectually, morally, politically—without surrendering our agency to external authorities.

This work requires intellectual courage, emotional maturity, and what I've called “love as an epistemic force”—the capacity to understand reality through sustained, caring attention rather than analytical reduction or mystical escape.

Peterson's definitional evasions don't just fail to contribute to this work—they actively undermine it by making it impossible to see what's actually at stake.

The Choice We Face

We face a choice in how we engage with questions of meaning, morality, and ultimate purpose. We can be honest about what we believe and why, accepting the risks that come with making specific claims. Or we can hide behind sophisticated evasions that give the appearance of profundity while avoiding the responsibilities of genuine belief.

We can do the hard work of creating new meaning-making frameworks adequate to our current moment. Or we can perform sophistication while avoiding the creative labor that real sophistication requires.

We can acknowledge that we are the meaning-makers—that this is both our burden and our privilege—and take responsibility for making meaning worthy of our lives. Or we can pretend that meaning comes from elsewhere while unconsciously shaping it through our own choices and attention.

Peterson has chosen evasion over engagement, performance over practice, the appearance of profundity over its substance. In doing so, he's wasted insights that could have contributed to the most important work of our time: learning to be fully human in a world where being human requires conscious choice rather than inherited script.

We can do better. We can engage with the crisis of meaning that Peterson has correctly identified while maintaining the intellectual honesty he consistently abandons. We can create new forms of secular liturgy, democratic wisdom, meaning-making practices that serve human flourishing without requiring intellectual dishonesty.

Two plus two equals four. There are twenty-four hours in a day. And sometimes the most sophisticated-sounding answer is just a complicated way of avoiding the simple, difficult work of creating meaning worthy of our lives.

The center can be held. But only if we're willing to hold it ourselves, consciously and courageously, rather than pretending someone else is holding it for us.

That's what clear thinking looks like. That's what intellectual honesty demands. And that's what Jordan Peterson, for all his insight into the problem, consistently refuses to provide as a solution.

We shall never surrender—not to the comfortable evasions of sophisticated bad faith, not to the false choice between traditional frameworks we can't believe and secular frameworks that won't sustain us. We can create something better. But only if we're willing to do the work that creation requires.

The tragedy of Jordan Peterson is that he sees the territory clearly but refuses to do the mapping. The opportunity for the rest of us is to pick up where his insights end and his evasions begin.

Great analysis, as always and I very much appreciate the depth of thought in your secular liturgy. I’d like to suggest a third alternative. Clear thinking that creates meaning, while at the same time being open to supra-natural possibilities. Why do some people feel transported in prayer or meditation? What urges a person to save another life at risk of their own? Can we have religious meaning-making that replaces God as figurehead with God as movement? Is sacrificial atonement necessary to save our world or does our real presence- at every moment - do that? Here’s how I answer the questions: 1. Do you believe in God? Yes, perhaps in a different way than most, are you curious to know how? 2. Do you think Jesus rose from the dead? Yes, in his spiritual nature, as we all may be able to do. When my beloved brother died tragically at 29 many years ago, my best friend had a vision of him at the end of her bed shaking her awake and saying “tell them I’m okay, just tell them I’m okay.” She said it was more real than real, and she has not feared death since. (My most practical and down to earth friend by the way, and the wife of a funeral director). Peter Fenwick’s research on this phenomenon is worth a look. 3. Would you lie to save innocent lives? Yes, without a moment’s hesitation, unless the lie would harm even more lives, then I would need more specific information.

I am so grateful you are in the world at this moment in time sharing your wisdom and thoughts. “Sustained, caring attention” is difficult and beautiful and what we truly need, and what nefarious forces are trying to take from us and erase. We must not let them